WALKING CORPORATE SUBURBIA

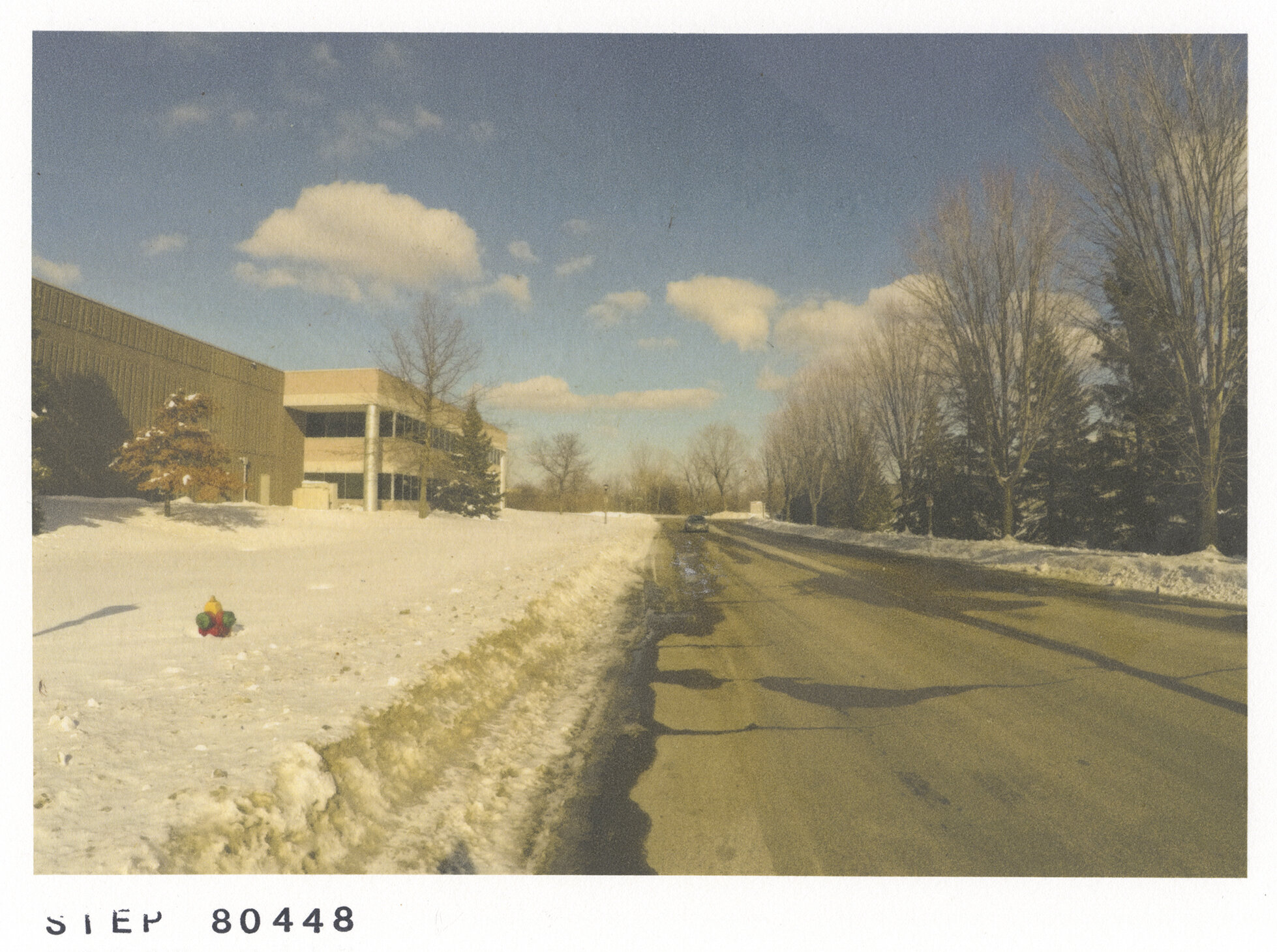

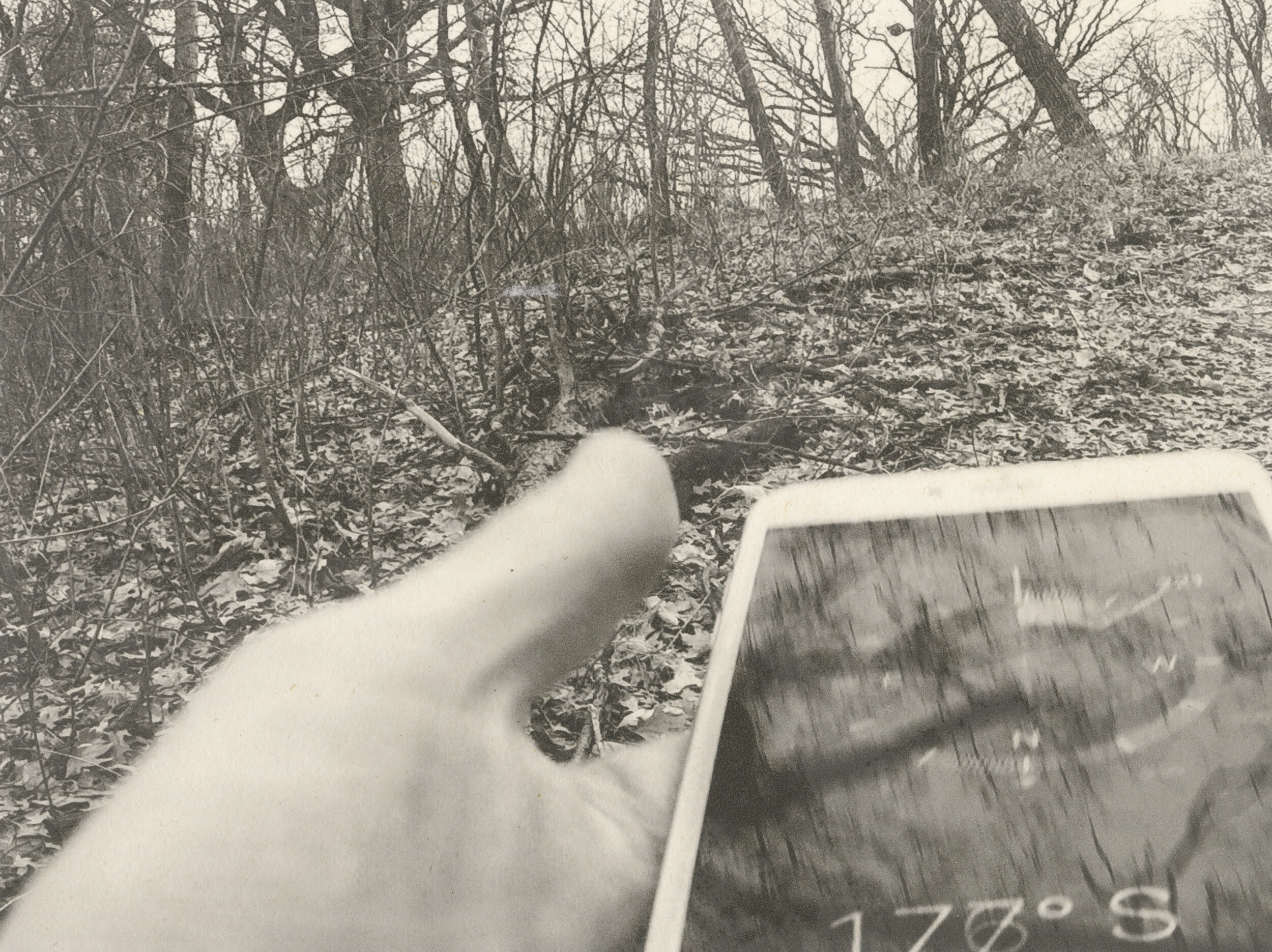

I walk between the dozen Fortune-500 corporate headquarters located in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan region. I use only a compass to navigate the multi-day treks through almost exclusively suburban space, recording my routes on a (hidden) GPS as I go, and wearing a GoPro camera that takes one picture every two seconds.

Some of the many mediations extending from this long-form walking project are documented below, along with (at the bottom) writing on the geographic rationale for this work.

ARTIST BOOK SUBURBÍSCITY

I re-mediate this trek into many forms. One major one is a 96-page artist book that I hand-printed using photogravure plates, each day of walking given a section in the book along with poetic annotations on the facing pages.

Please note the scanned versions of these pages look and feel significantly different from the printed book. Scroll down an inch for a collection of close-up, high-res scans from parts of the book.

A copy of the book (an edition of 6) has been acquired by the Francis V. Gorman Rare Art Book Collection at the University of Minnesota.

Holding a photo-polymer gravure plate in the printmaking darkroom at the University of Minnesota. Here I am drying the plate after exposing it, before hardening it and inking it to print in the intaglio press.

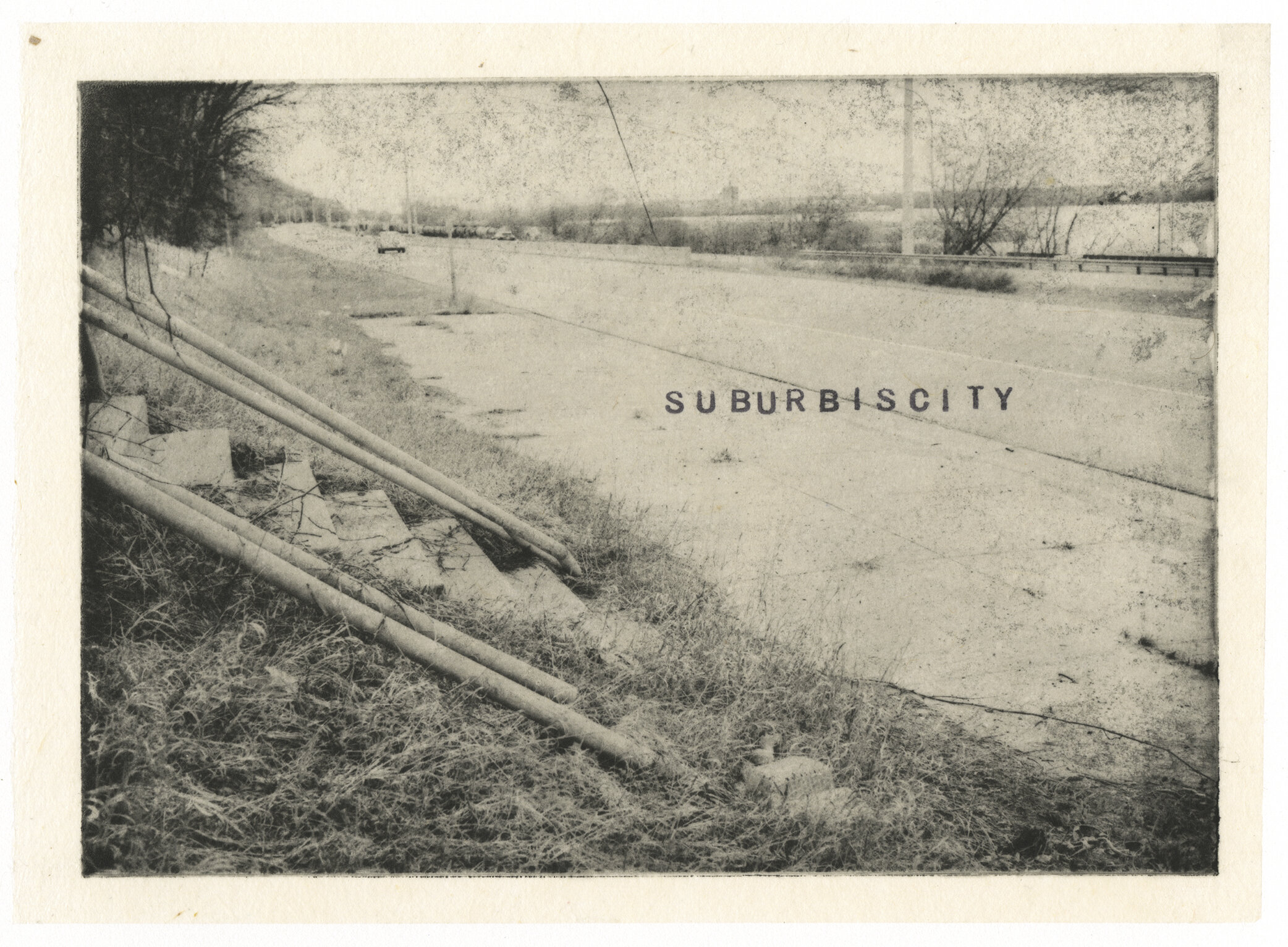

Employing a slow, methodical, labor-intensive printing process poetically echoes the deliberation of the walking enterprise. At the same time, this puts a 21st-century photographic technology in conversation with photogravure, a technology first used around 150 years ago. The disjuncture hints at what we might see when we slow down the hyper speed of the American urban economy. One thing we start to see are the spaces in between the seats of great economic power and wealth accumulation: the (sub)urban forms that sustain global capitalism. The images often showcase built landscapes in a way that inspires their re-imagining; what else might these lost corners of the metropolis be used for?

Click on the images below to open a slideshow of some of the pages from Suburbíscity.

Pulling a print from a lithography press after pressure gluing the image onto the backing page via chine collé. That sheet contains content on the front and back, such that when it’s folded once, it makes four pages. Using the pressure-activated glue (Rhoplex) allows me to avoid embossments on the pages.

INSTALLATION

In 2021 I created a gallery installation based on a futuristic, theatrically performed rendition of an institutional archive that has acquired, and is in the process of cataloging the circa 75,000 photographs that I took with a GoPro camera on my walks. The photogravure artist book plays a central role in this exhibit. I perform the role of an undead archivist drone, trapped, carrying out the tasks of something out of its control.

ARCHIVING THE VISUAL DATA

In collaboration with the Digital Conservancy’s Data Repository at the University of Minnesota, I published all of the circa 75,000 photographs, maps, voice memos, and sound recordings that I made on the walks. Access the repository HERE.

In this project art and life are intertwined. While I perform the role of an undead archivist drone in my installation working with these photos, the visual material is also archived in the present for all kinds of fictional or non-fictional use. I hope, for example, that the content will be useful for historians, demographers, urban planners, and economic geographers doing scholarship in the future. As an artist, I relish the slipperiness between a real and a fabricated archive, and am pleased that this kind of contribution to the conservancy is novel.

GEOGRAPHIC RATIOINALE

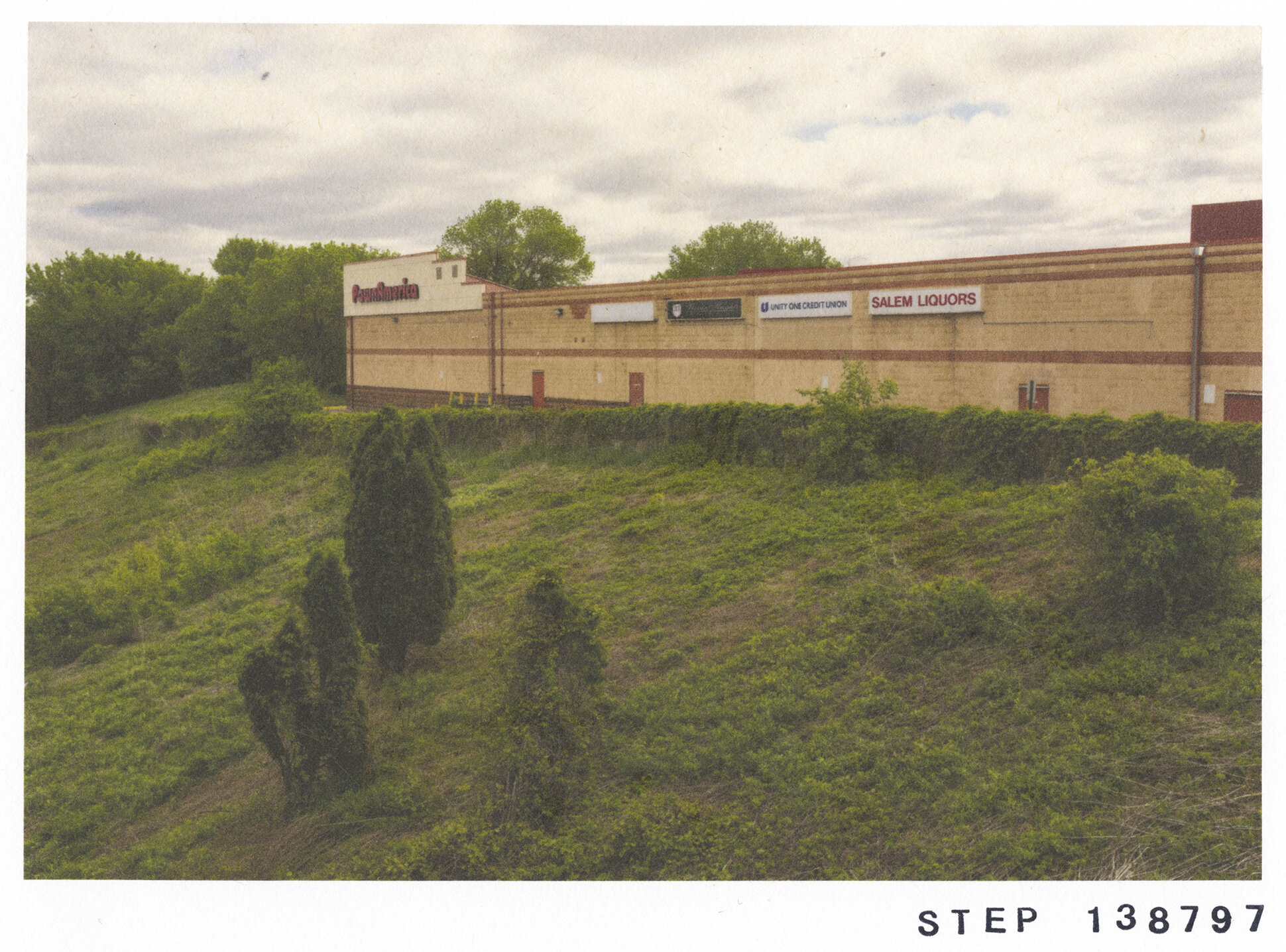

Any large scale economic system—capitalism, in this case—has a built form that emerges to accommodate the (dys)functions of that economy. The photographs produced on these walks seek to expose that built form, implicitly positing that the organization of suburban spaces is intimately tied to the needs, as it were, of the global corporations. These include things like high-speed roads, protected residential areas, and recreational opportunities like water bodies and parks. One can also read in this built form spaces of oppression and poverty, such as unmaintained housing and sidewalks, shuttered storefronts, and many instances of economic liminality, that is, places for people who are involved in the economic system without much choice, but are not its beneficiaries. One of the great consequences of capitalism is its tendency to direct wealth and resources into smaller and smaller numbers of people as time progresses. This can be read in the urban form, and this collection provides snapshots of this movement towards unequal wealth distribution as it existed in these years.

The headquarters between which I walk are the main decision, management, finance, and research centers for large-revenue companies that impact the lives of millions of people across the local region, the nation, and the world. While the majority of lives—bodies, even, as in the case of health insurance and food manufacturing—are materially shaped by these entities, most people could not say where they are located within the city and its peri-urban hinterlands. Examples of these companies, along with their annual revenues in 2019, are UnitedHealth Group ($242 billion), 3M ($32 billion), Ecolab ($15 billion), CHS ($32 billion), C.H. Robinson ($15 billion), Cargill (privately held, $115 billion), Best Buy ($43 billion), United Natural Foods Inc ($21 billion), Target ($75 billion), and General Mills ($18 billion).

There are two intersecting axes I deal with in this project. The first is the corporate headquarter, and the second is the suburb. Each of these phenomena addresses 21st-century global capitalism and its new urban geographies. Specifically, what interests me is how the aesthetic devaluation of suburbs in the 1980s and 90s coincided with increased access to suburbs by lower-income strata of the population (Nijman, Suburban Governance, 2015). By 2019, over one-third of the U.S. suburban population is classified as “non-white,” a demographic shift that dovetails with the increased suburban siting of large corporate headquarters. Immigrant enclaves, cheaper real estate, and self-contained economies that do not rely on central business districts are forging new types of spaces that don’t match with notions of “urban” or “suburban.”

In Walking Histories (2016), Julie Hipperson points out that walking has often been associated with “impoverished and landless members of rural society.” To walk between these global giants is to conjure an allegiance with the landless and powerless, pointing toward the increasing national and global wealth disparity that the corporations implicitly (or directly) enable and promote.

Suburbia is an urban jungle to the foot traveler: unconnected, unknown, frightening, off-putting, dangerous, or boring. The leftover design of suburban landscapes has engendered an awkwardness in human-scale locomotion (see Dunham-Jones, 2009, “Retrofitting Suburbia”). Built for vehicles and point-to-point travel, the ether, or space in-between, is a seemingly infinite, forgotten plane, those which do not serve as meaningful destinations. It is on this unlikely plane where I imagine new futures of resistance to unfold, from meeting places to lemonade stands, and from freeway interchange plazas to roadside botanical gardens.

This is Pop art, embodied and performed. It is a reflection of who we are as a society, whatever our opinion about corporations, writ large, might be. (Before being too judge-y, remember that Instagram, the mode of communication a la mode for artists in 2020 and beyond, is just one part of a corporation that is larger than any of these in the Twin Cities, with UnitedHealth being the only exception.) This is not a celebration of corporate life or of the normalization of wealth accumulation, nor does it condone the historically (and currently) racist social systems that make continuously accelerating commercial growth possible at a global scale. On the contrary, it is an attempt to point attention--much as Pop art might have--toward the realities of economic geography, in an attempt to know them and sow the seeds of rebuilding them in ways that benefit all people.

My identity as a middle-aged, white, English-speaking, employed, housed, U.S.-passport-holding male positions me to blend-in, as it were, when I walk through areas that do not experience high volumes of foot traffic from “outsiders.” That is, even with a strapped-on camera, I look enough like a local to not arouse visits from the police, or suspicion from other entities that enforce social and economic boundaries. Being ignored is a privilege that only proves the existence of the racist structure in the first place; I suspect that someone pushing a grocery cart, or someone with a camera strapped to a turban, would not move as unencumbered as I have.

When I walk, I often find myself trying to imagine the landscape as it might have looked before European contact with the Americas. Without assuming details about the Dakota experience, I think about lives that might have been lived in these places. With each picture, I see what now appear to be banal landscapes as deep containers that have amassed generational layers of meaning. That is, stories about real people who held all the complexities, fears, joys, and wonders of a life fully lived have happened in the places where my feet hit the ground, where motorists fling out cigarette butts and where plows heap oil- and salt-soaked snow.