In July 2020 I had the chance to take a course called Documentary Comics, taught at the Minnesota Center for Book Arts by Camilo Aguirre. Camilo is a graduate of the M.F.A. program at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, hails from Colombia, and specializes in political documentary-creative comics. Being entirely new to both the comics and the drawing universes, I can safely say that I learned a TON from Camilo, whose knowledge and philosophy of comics is built from a strong foundation, punctuated by vast experience with Latin and South American trends in political comics.

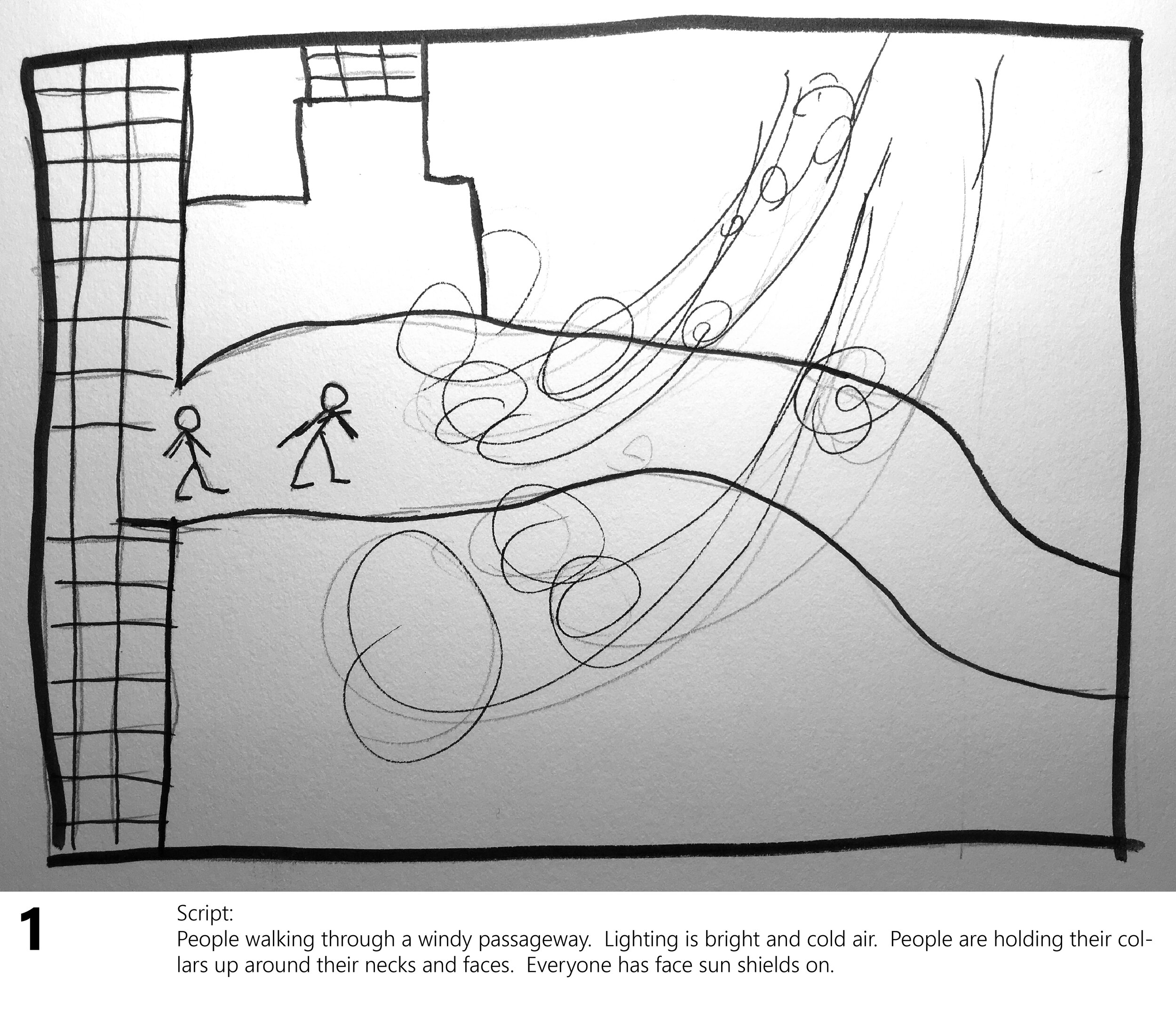

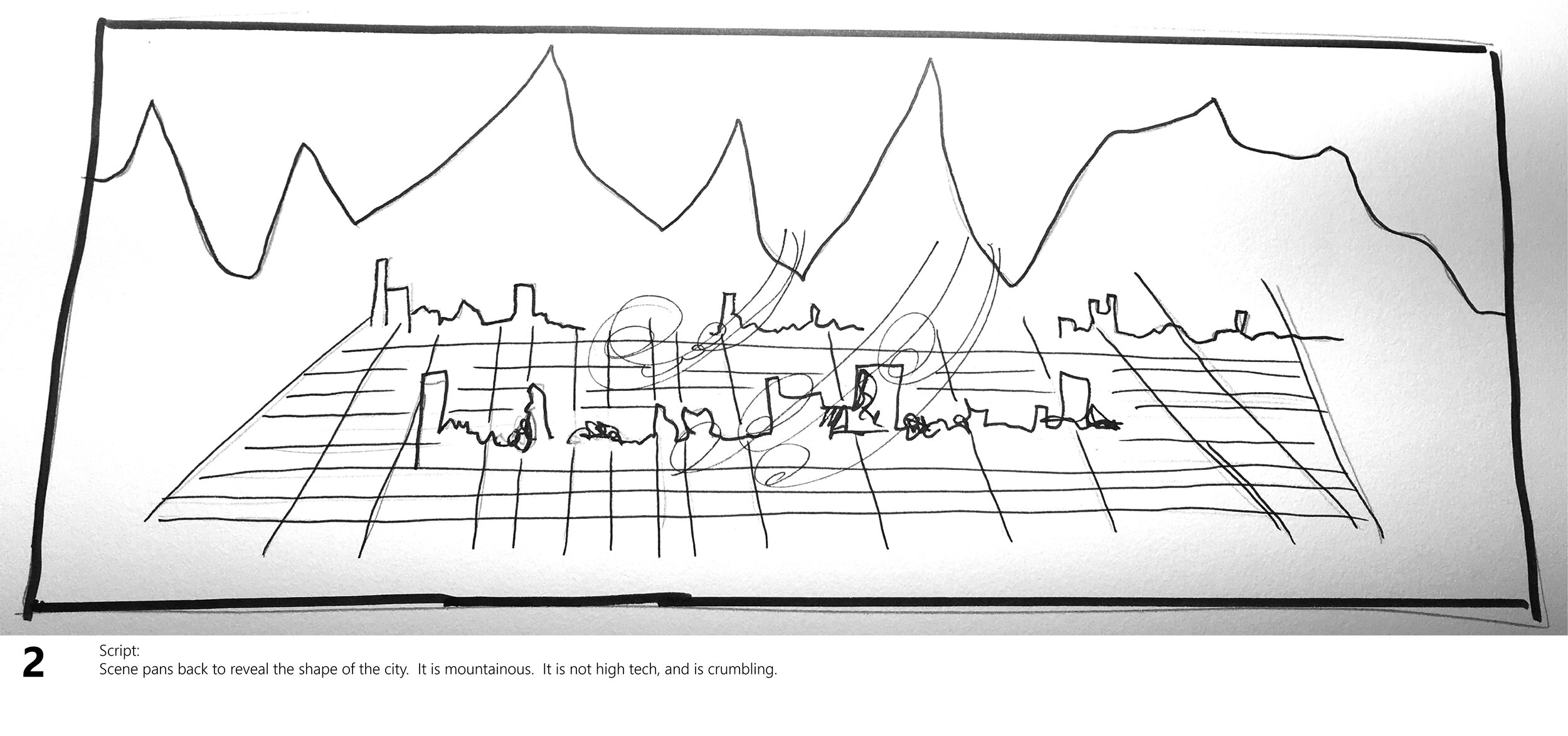

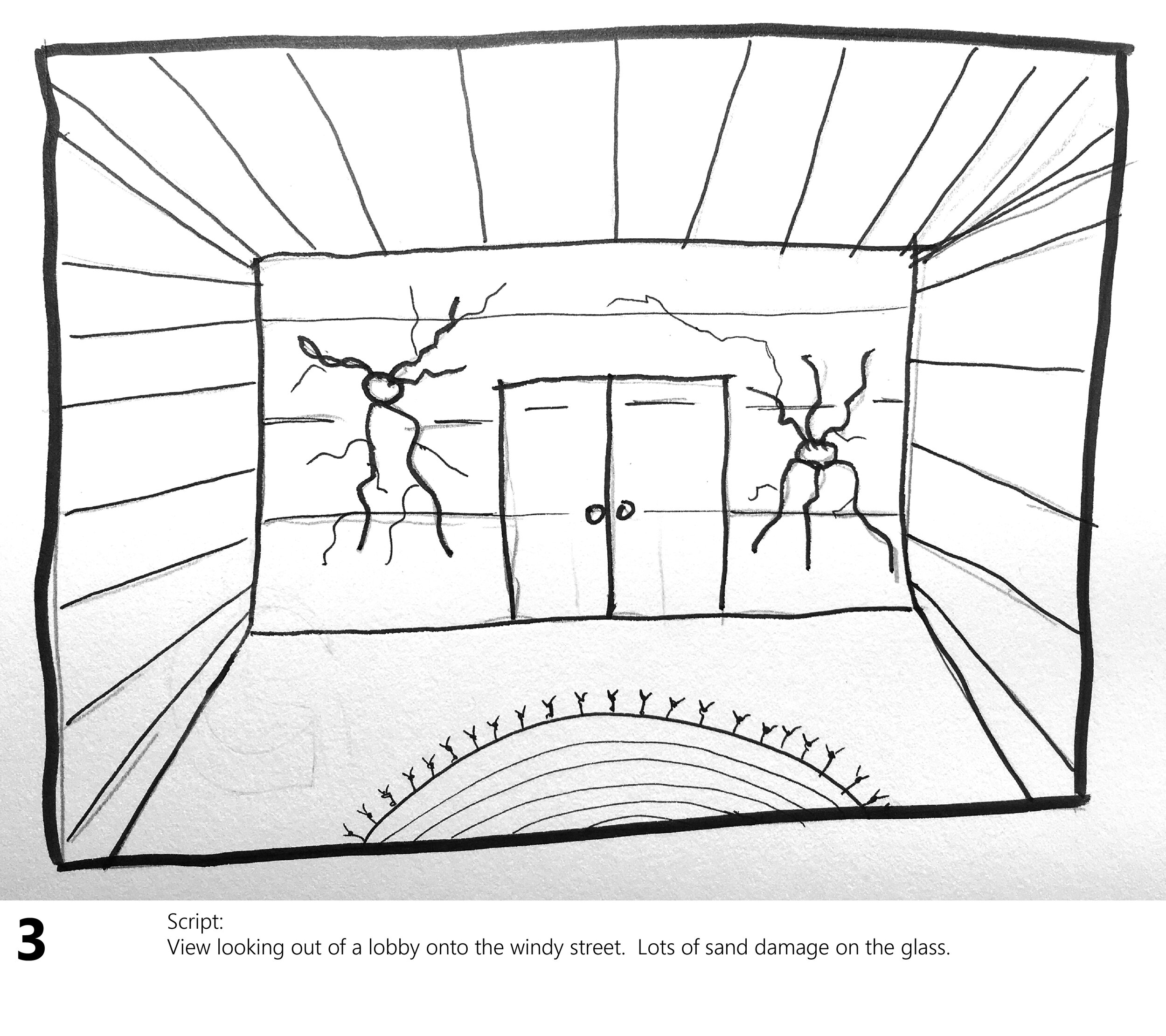

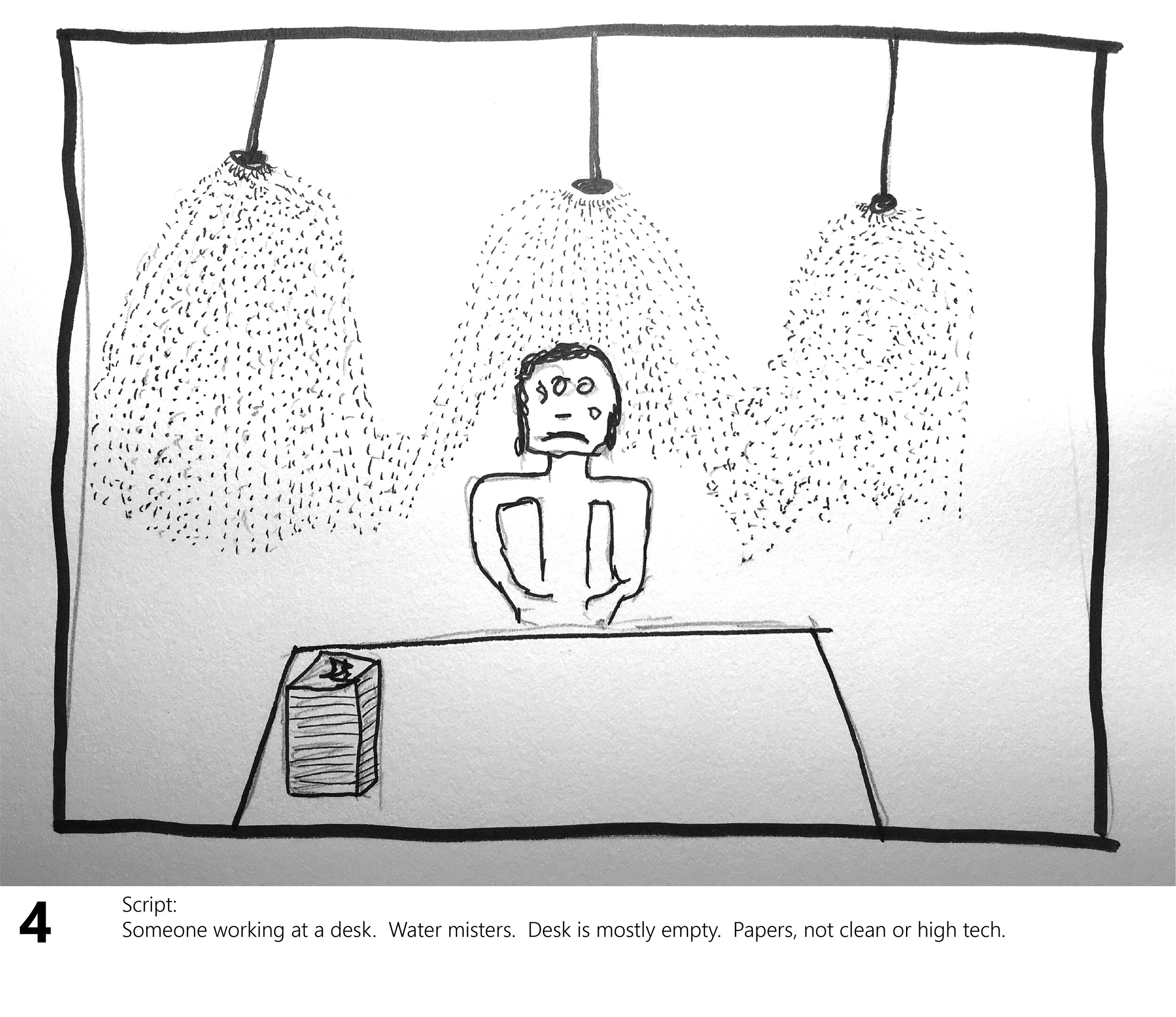

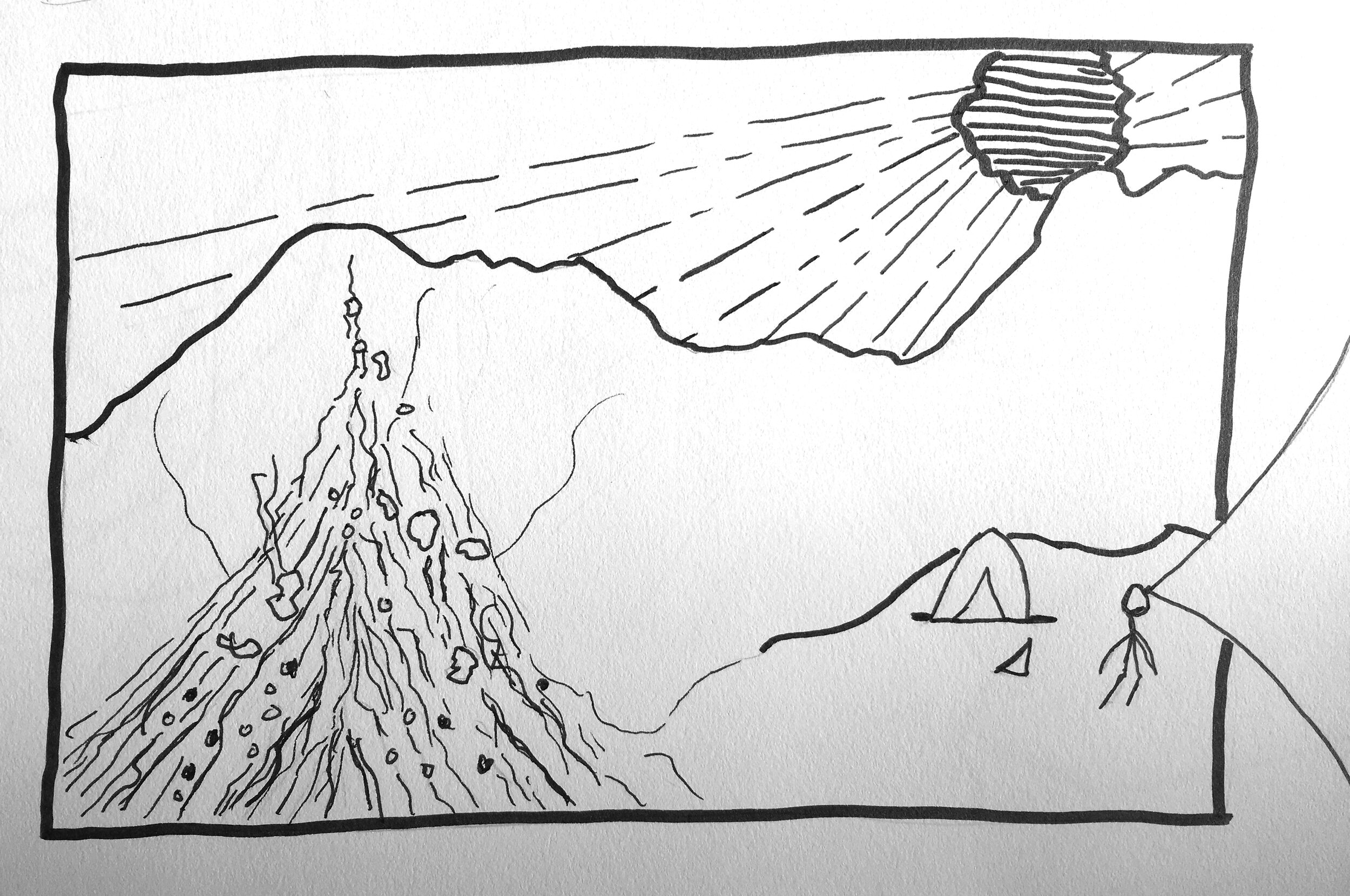

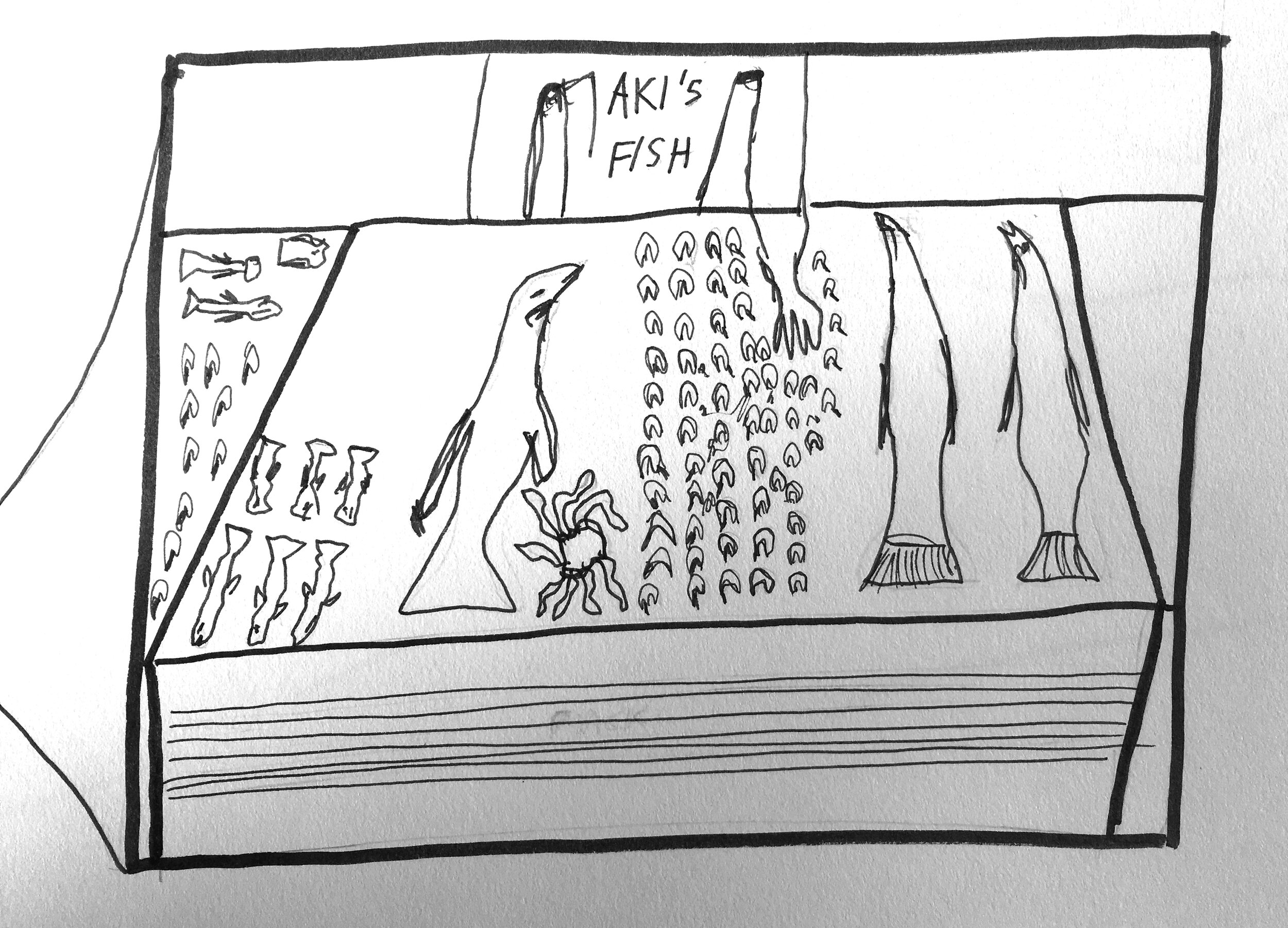

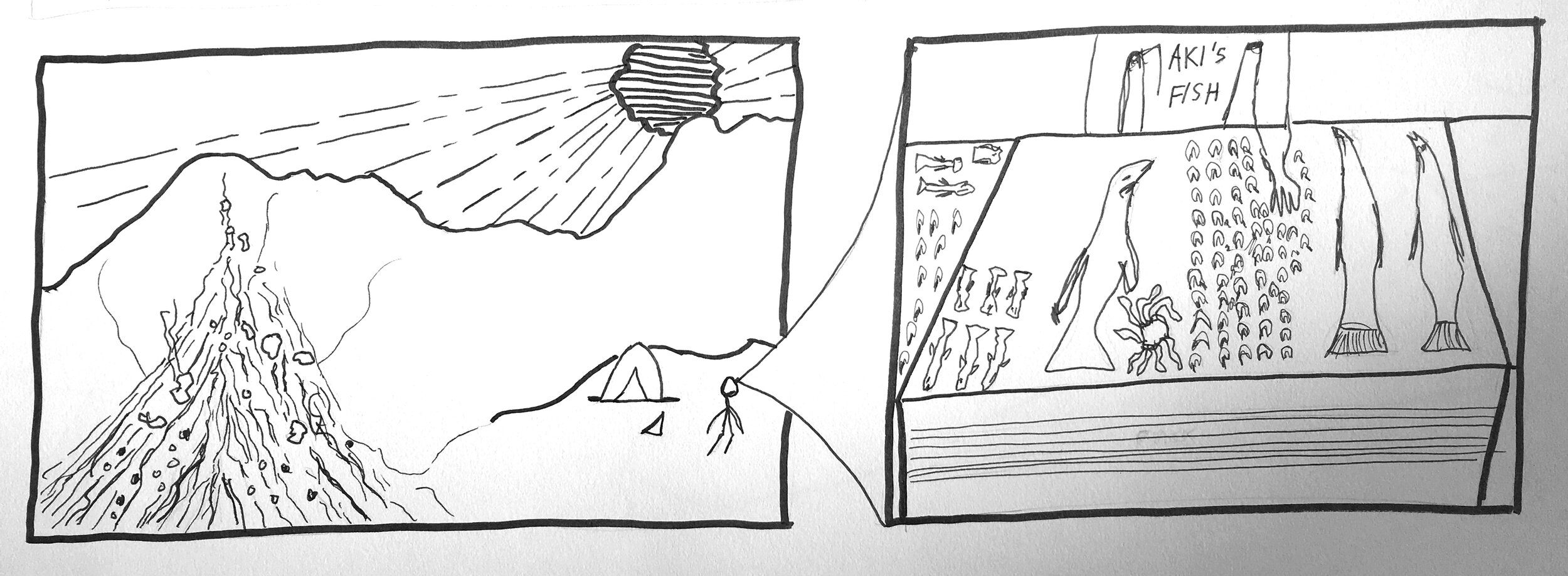

One of the main things I learned is that drawing comics does not require great skill in drawing, a liberating approach that instead focuses on content and storytelling. I was able to get my little tiny comics practice off the ground for a few moments, and some of those results are below.

The other huge benefit of this class was gaining access to Camilo’s (and the class’s) bibliography of online lectures and comic book artists. Overtaken by a spell of archival madness, I’ve decided to list all of the references from our class below, with links whenever possible.

CONVERSATIONS WITH COMICS PROS

In a chapter-by chapter study, leading comic critic Hillary Chute and New Yorker writer Sarah Larson discuss Chute's new book, Why Comics?.

This is an interview with Scott McCloud. One of his main points is that comics are all about what happens in between the panels, i.e. in the gutters. It’s important that the reader connect some of the dots as means of engagement, or call and response.

A 2013 Artist Talk moderated by Charlie Smith. Joe Sacco's comics are entirely unique in the field.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Latin and South America Based Material

Scorer, James (ed.). 2020. Comics Beyond the Page in Latin America.

Cossio, Jesus. 2010. Barbarie: Comics sobre violencia política en el Perú, 1985-1990.

Catalá-Carrasco, Jorge L., Paulo Drinot, and James Scorer. 2017. Comics and memory in Latin America.

Reyes, Carlos and Rodrigo Elgueta. 2015. Los Años de Allende: Novela gráfica.

Hernandez, Gilbert, Jaime Hernandez, and Mario Hernandez. 1982-present. Love and Rockets.

Cossio, Jesus, Luis Perry, and Alfredo Lurquin. 2009. Rupay: Historias de la violencia política en Perú, 1980-1984.

Non Latin American Artists

Harder, Jens. 2015. Alpha: ...Directions.

Pekar, Harvey. 1976-2008. American Splendor.

Krug, Nora. 2018. Belonging: A German reckons with history and home.

Thompson, Craig. 2016. Blankets: A graphic novel.

Ware, Chris. 2012. Building Stories.

Eisner, Will. 2008. Comics and Sequential Art: Principles and practices from the legendary cartoonist.

Ghosh, Vishwajyoti. 2010. Delhi Calm.

Delisle, Guy, 2004. Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea.

Mignola, Mike. 1994-2019. Hellboy Universe.

Spiegelman, Art. 1980-1991. Maus.

Satrapi, Marjane. 2003. Persepolis.

Sattouf, Riad. 2015. The Arab of the Future: Growing up in the Middle East (1978-1984).

Guibert, Emmanuel, Didier Lefevre, and Frederic Lemerecier. 2009. The Photographer.

Talbot, Bryan. 2008. The Tale of One Bad Rat.

Hergé. 1929-1976. The Adventures of Tin Tin.

Soltani, Amir, and Khalil. 2011. Zahra's Paradise.

DeForge, Michael. 2014. Ant Colony.

Abel, Jessica. 2017. Trish Trash: Rollergirl of Mars.

Bell, Gabrielle. 2020. Inappropriate.

Juliacks. 2017. Architecture of an Atom.

Calpurnio. 2016. Mundo Plasma.

Manga

Yokoyama, Yuichi. 2013. World Map Room.

Secondary Literature and How-To

Kunka, Andrew. 2018. Autobiographical Comics.

Chute, Hillary. 2016. Disaster Drawn: Visual witness, comics, and documentary form.

Mickwitz, Nina. 2016. Documentary Comics: Graphic truth-telling in a skeptical age.

Willberg, Kriota. 2018. Draw Stronger: Self-care for cartoonists & visual artists.

Chaney, Michael. 2011. Graphic Subjects: Critical essays on autobiography and graphic novels.

Barry, Lynda. 2019. Making Comics.

Fingeroth, Danny. 2008. The Rough Guide to Graphic Novels.

McCloud, Scott. 1993. Understanding Comics: The invisible art.

Chute, Hillary. 2017. Why Comics?: From underground to everywhere.

Madden, Matt. 2005. 99 Ways to Tell a Story: Exercises in Style.

Wood, Wally. 1980. 22 Panels That Always Work.

Publishers and Shops & etc.

Drawn & Quarterly

Fantagraphics

Uncivilized Books

XKCD

The Nib

“DESERT CITY”

by Nicholas Bauch, 2020